Regarding the Oil Paintings (Artist Statement for the Homage to the Masters Solo Exhibition)

This group of works developed and branched out from the concept of "following the brush." Their starting point was two pieces in homage to Alberto Giacometti's "Walking Man." Throughout his life, many of Giacometti's works depicted the loneliness and alienation of modern humans, strangers unrelated to their time and space, and mutually unfamiliar. Even without support, he did not choose religious salvation, but simply gazed at human existence, circumstances, and phenomena—simply gazed. These reflections resonate deeply with my own experiences practicing Buddhism. Corresponding works include sculptures such as "Walking Man," "Crawling Man," "Five Figures Walking on a Square," and "My Left Hand," while paintings include the sister works "Woman Sitting on a Chair" and "Man Sitting by a Bed." In these, the remaining stub of a pencil and the used-up paint tubes reveal traces of life or the absence of the soul. Also inspiring me were two of Giacometti's life photographs: "Giacometti Lying on the Snow at Night" and "Giacometti Sitting Below an Alpine Peak." One shows Giacometti lying large on the snow, looking up at the dark sky enveloping him, and the other captures him in his youth, shirtless, sitting below a mountain summit during a climb in the Alps. Here, I sincerely pay homage to him. The young Giacometti surely did not know that his later art would so deeply touch those who also felt like strangers, their souls seemingly unrelated to their time and space.

Based on the perspective of "gazing at death," I drew my thoughts to Rembrandt's and Chaïm Soutine's animal carcasses, Rembrandt's "The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp," Andrea Mantegna's "Lamentation over the Dead Christ," Hans Holbein the Younger's "The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb," and Edouard Manet's "The Dead Toreador." In Western art history, paintings of animal corpses or bones are related to the European "Vanitas" tradition, all reminding viewers that no matter how beautiful or good the fleeting world is, we will die, and ultimately must die. The foundation of existentialist philosophy is built upon this, and it is quite similar to the Buddhist view of impermanence.

Another branch of my thinking focuses on the theme of landscape, inspired by Caspar David Friedrich's "Wanderer above the Sea of Fog" and "The Chalk Cliffs on Rügen," and Arnold Böcklin's "Isle of the Dead." Originally, Caspar David Friedrich's paintings had a sense of conquering nature and marveling at its wonders, while Arnold Böcklin's paintings depict the imagined place where souls go after death. I deliberately used the feel and brushstrokes of ink wash painting to depict these landscapes, and utilized the proportions of paint tubes and the canvas to show the ideal in the Chinese mind of always wanting to be one with heaven and earth, and to find peace and existence by following one's insignificance.

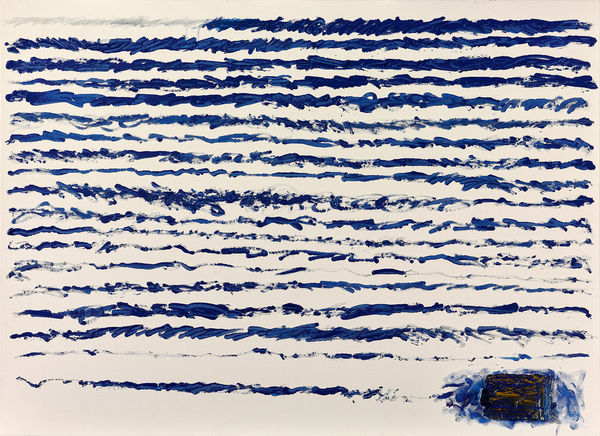

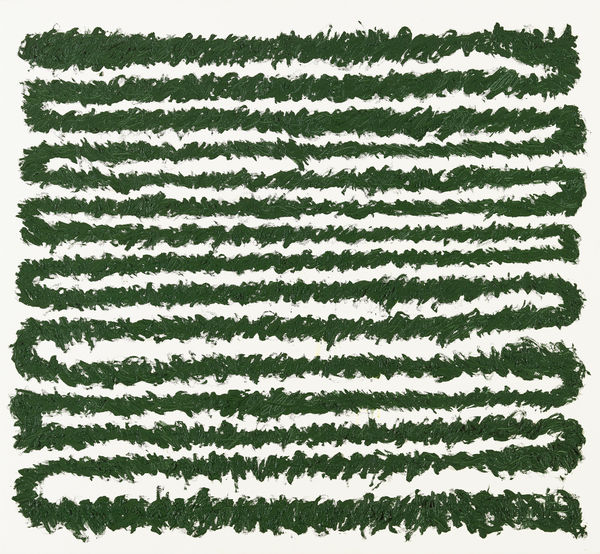

In addition to paying homage to masters and classics of visual art, I have also extended to literary figures and musicians. For example, "The Myth of Sisyphus" related to Albert Camus, and Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57, "Appassionata." The work "The Myth of Sisyphus" expresses the fate of endless toil in life, reflecting on the presence or absence of meaning in struggle. Since 2015, I have created the "Lines of Musical Sounds" series, once expressing classical music such as Tchaikovsky's Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50, and Bruch's Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46, through abstract lines. The selected piece for this exhibition is Beethoven's "Appassionata" piano sonata. In any case, let us pay homage to the masters.

關於油畫作品(向大師致敬個展展覽自述)

是從走筆的概念發展衍生一群作品,它們的起始是兩件我向賈克梅蒂Alberto Giacometti致敬的《行走的人》,賈克梅蒂一生很多作品都在表現現代人類孤單、疏離、與所處時空無關且互為陌路的異鄉人,即使無依無靠,他並不選擇宗教的救贖,只是凝視人類的存有、處境與現象,只是凝視。這些省思,與我自己修習佛教的經驗有非常高的重合。與之相應的作品有〈行走的人〉、〈爬行的人〉、〈五個在廣場上行走的人〉、〈我的左手〉等雕塑作品,而繪畫形式的則有〈坐在椅子上女人〉、〈坐在床邊的男人〉姊妹作,作品中鉛筆剩餘的尾巴與用盡的顏料錫管顯示生命的遺跡或靈魂的缺席。還有啟發自兩張賈柯梅蒂的生活照《夜間躺在的雪地上的賈柯梅蒂》、《坐在阿爾卑斯山峰下的賈柯梅蒂》,一張是賈柯梅蒂大字躺在雪地仰天望著籠罩他的黑暗天空,另一張是他年輕攀登阿爾卑斯山時拍的,光著膀子坐在山巔下。在這裡,我是真誠的向他致敬,年輕時的他,一定不知道他後來的藝術,竟能深深觸動同樣感覺自己的靈魂與所處的時空好似毫無關係的異鄉人。

基於「凝視死亡」的觀點,我把思路拉到了林布蘭Rembrandt及蘇丁Chaïm Soutine動物的屠體,林布蘭Rembrandt的《尼古拉斯•杜爾博醫師的解剖課》,安德烈亞•曼特尼亞Andrea Mantegna《哀悼死去的基督》,Hans Holbein der Jüngere小漢斯•霍爾拜因的《基督在陵墓中的屍體》、愛德華•馬奈Edouard Manet的《死亡的鬥牛士》。西方藝術史繪畫動物屍體或骨頭與歐洲Vanity的傳統思維有關,它們都在點醒觀者,浮華世界再美再好,可我們會死,也終究要死。存在主義哲學反思的地基是建築在此的,而這與佛教的無常觀亦頗為近似。

我思考的另外一條支線是風景面向的主題,卡斯巴•大衛•佛烈德利赫Caspar David Friedrich的《霧海上的行者》、《呂根島上的白堊岩》及阿諾德•勃克林Arnold Böcklin的《死之島》。本來卡斯巴•大衛•佛烈德利赫的畫的觀點有點征服自然、驚嘆自然奇觀的意思,阿諾德•勃克林的畫有死後靈魂去處的想像,我故意用水墨的感覺與筆法來畫這些風景畫,並利用顏料錫管與畫幅的比例顯示中國人心靈的理想上始終想與天地自然合而為一,並且隨順渺小的安身立命。

除了向視覺藝術的大師及經典致敬外,我還拓展至文學家與音樂家。比如與阿爾貝•卡繆Albert Camus相關的《薛西弗斯之山》,以及貝多芬Ludwig van Beethoven第57號作品F小調第23號鋼琴奏鳴曲《熱情》。作品《薛西弗斯之山》表達人生無盡勞苦的宿命,省思奮鬥意義的有與無。自2015年開始我創作了「樂音的線條」系列,曾經把柴可夫斯基作品50號《A小調鋼琴三重奏》及布魯赫作品46號《蘇格蘭幻想曲》等古典音樂,以抽象線條表現出來。本次我選定的曲目是貝多芬的《熱情》鋼琴奏鳴曲。不論如何,向大師們致敬吧。

This group of works developed and branched out from the concept of "following the brush." Their starting point was two pieces in homage to Alberto Giacometti's "Walking Man." Throughout his life, many of Giacometti's works depicted the loneliness and alienation of modern humans, strangers unrelated to their time and space, and mutually unfamiliar. Even without support, he did not choose religious salvation, but simply gazed at human existence, circumstances, and phenomena—simply gazed. These reflections resonate deeply with my own experiences practicing Buddhism. Corresponding works include sculptures such as "Walking Man," "Crawling Man," "Five Figures Walking on a Square," and "My Left Hand," while paintings include the sister works "Woman Sitting on a Chair" and "Man Sitting by a Bed." In these, the remaining stub of a pencil and the used-up paint tubes reveal traces of life or the absence of the soul. Also inspiring me were two of Giacometti's life photographs: "Giacometti Lying on the Snow at Night" and "Giacometti Sitting Below an Alpine Peak." One shows Giacometti lying large on the snow, looking up at the dark sky enveloping him, and the other captures him in his youth, shirtless, sitting below a mountain summit during a climb in the Alps. Here, I sincerely pay homage to him. The young Giacometti surely did not know that his later art would so deeply touch those who also felt like strangers, their souls seemingly unrelated to their time and space.

Based on the perspective of "gazing at death," I drew my thoughts to Rembrandt's and Chaïm Soutine's animal carcasses, Rembrandt's "The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp," Andrea Mantegna's "Lamentation over the Dead Christ," Hans Holbein the Younger's "The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb," and Edouard Manet's "The Dead Toreador." In Western art history, paintings of animal corpses or bones are related to the European "Vanitas" tradition, all reminding viewers that no matter how beautiful or good the fleeting world is, we will die, and ultimately must die. The foundation of existentialist philosophy is built upon this, and it is quite similar to the Buddhist view of impermanence.

Another branch of my thinking focuses on the theme of landscape, inspired by Caspar David Friedrich's "Wanderer above the Sea of Fog" and "The Chalk Cliffs on Rügen," and Arnold Böcklin's "Isle of the Dead." Originally, Caspar David Friedrich's paintings had a sense of conquering nature and marveling at its wonders, while Arnold Böcklin's paintings depict the imagined place where souls go after death. I deliberately used the feel and brushstrokes of ink wash painting to depict these landscapes, and utilized the proportions of paint tubes and the canvas to show the ideal in the Chinese mind of always wanting to be one with heaven and earth, and to find peace and existence by following one's insignificance.

In addition to paying homage to masters and classics of visual art, I have also extended to literary figures and musicians. For example, "The Myth of Sisyphus" related to Albert Camus, and Ludwig van Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57, "Appassionata." The work "The Myth of Sisyphus" expresses the fate of endless toil in life, reflecting on the presence or absence of meaning in struggle. Since 2015, I have created the "Lines of Musical Sounds" series, once expressing classical music such as Tchaikovsky's Piano Trio in A minor, Op. 50, and Bruch's Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46, through abstract lines. The selected piece for this exhibition is Beethoven's "Appassionata" piano sonata. In any case, let us pay homage to the masters.

關於油畫作品(向大師致敬個展展覽自述)

是從走筆的概念發展衍生一群作品,它們的起始是兩件我向賈克梅蒂Alberto Giacometti致敬的《行走的人》,賈克梅蒂一生很多作品都在表現現代人類孤單、疏離、與所處時空無關且互為陌路的異鄉人,即使無依無靠,他並不選擇宗教的救贖,只是凝視人類的存有、處境與現象,只是凝視。這些省思,與我自己修習佛教的經驗有非常高的重合。與之相應的作品有〈行走的人〉、〈爬行的人〉、〈五個在廣場上行走的人〉、〈我的左手〉等雕塑作品,而繪畫形式的則有〈坐在椅子上女人〉、〈坐在床邊的男人〉姊妹作,作品中鉛筆剩餘的尾巴與用盡的顏料錫管顯示生命的遺跡或靈魂的缺席。還有啟發自兩張賈柯梅蒂的生活照《夜間躺在的雪地上的賈柯梅蒂》、《坐在阿爾卑斯山峰下的賈柯梅蒂》,一張是賈柯梅蒂大字躺在雪地仰天望著籠罩他的黑暗天空,另一張是他年輕攀登阿爾卑斯山時拍的,光著膀子坐在山巔下。在這裡,我是真誠的向他致敬,年輕時的他,一定不知道他後來的藝術,竟能深深觸動同樣感覺自己的靈魂與所處的時空好似毫無關係的異鄉人。

基於「凝視死亡」的觀點,我把思路拉到了林布蘭Rembrandt及蘇丁Chaïm Soutine動物的屠體,林布蘭Rembrandt的《尼古拉斯•杜爾博醫師的解剖課》,安德烈亞•曼特尼亞Andrea Mantegna《哀悼死去的基督》,Hans Holbein der Jüngere小漢斯•霍爾拜因的《基督在陵墓中的屍體》、愛德華•馬奈Edouard Manet的《死亡的鬥牛士》。西方藝術史繪畫動物屍體或骨頭與歐洲Vanity的傳統思維有關,它們都在點醒觀者,浮華世界再美再好,可我們會死,也終究要死。存在主義哲學反思的地基是建築在此的,而這與佛教的無常觀亦頗為近似。

我思考的另外一條支線是風景面向的主題,卡斯巴•大衛•佛烈德利赫Caspar David Friedrich的《霧海上的行者》、《呂根島上的白堊岩》及阿諾德•勃克林Arnold Böcklin的《死之島》。本來卡斯巴•大衛•佛烈德利赫的畫的觀點有點征服自然、驚嘆自然奇觀的意思,阿諾德•勃克林的畫有死後靈魂去處的想像,我故意用水墨的感覺與筆法來畫這些風景畫,並利用顏料錫管與畫幅的比例顯示中國人心靈的理想上始終想與天地自然合而為一,並且隨順渺小的安身立命。

除了向視覺藝術的大師及經典致敬外,我還拓展至文學家與音樂家。比如與阿爾貝•卡繆Albert Camus相關的《薛西弗斯之山》,以及貝多芬Ludwig van Beethoven第57號作品F小調第23號鋼琴奏鳴曲《熱情》。作品《薛西弗斯之山》表達人生無盡勞苦的宿命,省思奮鬥意義的有與無。自2015年開始我創作了「樂音的線條」系列,曾經把柴可夫斯基作品50號《A小調鋼琴三重奏》及布魯赫作品46號《蘇格蘭幻想曲》等古典音樂,以抽象線條表現出來。本次我選定的曲目是貝多芬的《熱情》鋼琴奏鳴曲。不論如何,向大師們致敬吧。

-

Pen Walking #158, 2016

Pen Walking #158, 2016 -

Pen Walking #92, 2011

Pen Walking #92, 2011 -

Pen Walking #156, 2016

Pen Walking #156, 2016 -

Pen Walking #157, 2016

Pen Walking #157, 2016 -

Pen Walking #162, 2016

Pen Walking #162, 2016 -

Pen Walking #164, 2016

Pen Walking #164, 2016 -

Sick Old Man on his Bed, 2016

Sick Old Man on his Bed, 2016 -

Prison-1, 2016

Prison-1, 2016 -

Pen Walking #159, 2016

Pen Walking #159, 2016 -

Walking in the Alley Alongside the Railway, 2016

Walking in the Alley Alongside the Railway, 2016 -

The Entrance of 386 Lane, 2016

The Entrance of 386 Lane, 2016 -

Bodrum Beach, 2016-2017

Bodrum Beach, 2016-2017 -

A Walking Man, Tribute to Alberto Giacometti - 1, 2016-2017

A Walking Man, Tribute to Alberto Giacometti - 1, 2016-2017 -

Three Men Walking, Tribute to Alberto Giacometti - 2, 2016-2017

Three Men Walking, Tribute to Alberto Giacometti - 2, 2016-2017 -

A Self-Portrait with Scissors, 2016-2017

A Self-Portrait with Scissors, 2016-2017 -

The Dead Toreador, 2019

The Dead Toreador, 2019 -

A Man Who Meditating above Himself, 2018-2019

A Man Who Meditating above Himself, 2018-2019 -

A Crawling Man, 2018-2019

A Crawling Man, 2018-2019 -

How It Ends, 2018-2019

How It Ends, 2018-2019 -

Sisyphus, 2017-2019

Sisyphus, 2017-2019 -

Five Walkers in the Square , 2018-2019

Five Walkers in the Square , 2018-2019 -

Carcass of Beef , 2019

Carcass of Beef , 2019